Given the vast amounts of funding required to finance the transition of our economies, these new bonds, which raise money not for a specific project but for a company to implement its overall sustainable transition strategy, are increasingly being used. Each SLB must define a specific set of Sustainability Performance Targets (SPTs) and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). Should the issuer not meet these predefined sustainability objectives within the set timeframe, certain penalties come into play, including for example, the raising of the interest rate paid to investors via a coupon step-up. These penalties aim to ensure that issuers of SLBs deliver on their commitments.

There has been a marked increase in the number of companies committed to reducing their emissions and becoming more environmentally friendly. It is now estimated that one in five of the world’s major listed companies has committed to becoming carbon neutral. This desire to move resolutely towards net zero is also reflected in the search for new financing methods to achieve these objectives, such as SLBs. According to figures published at the end of April by the Climate Bonds Initiative, the SLB market grew by no less than 941% over the course of 2021. At the end of last year, the total market reached USD 135 billion with issuance during the year amounting to USD 118.8 billion.

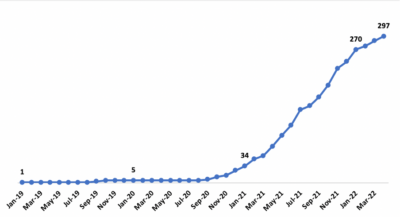

Recognising these new products since the publication of the Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles by the International Capital Market Association in June 2020, the Luxembourg Stock Exchange (LuxSE) is also seeing rapid growth in the number of SLB issued globally. “At the end of 2021, there were 246 SLBs listed worldwide, including 138 in Europe. At the end of April this year, global SLB issuance passed the 300 bonds mark, which represents a further increase of 25%,” observes Laetitia Hamon, Head of Sustainable Finance at LuxSE. On the Luxembourg Green Exchange (LGX), LuxSE’s platform dedicated to sustainable securities, 59 SLBs were already displayed at the end of April and, according to Hamon, the positive growth is expected to continue.

Source: LGX

“Companies from specific sectors, especially large emitters of greenhouse gases, have made important transition commitments and are taking concrete action in this direction. For this group of issuers, an SLB is a very interesting tool as it links a company’s sustainability objectives and financing strategy in a new way”, continues Hamon. And, in general, insofar as green bonds will not be sufficient to curb climate change and meet the considerable challenges of global warming, having new financial tools is critical to accelerate the green transition.

Unlike green bonds, which finance specific green projects, SLBs raise financing for general corporate purposes, and the issuer does not disclose how the proceeds are allocated. However, the SLB Principles have defined obligations that should prevent the temptation to greenwash.

In the initial phase of the issuance, the issuer must define KPIs. These KPIs must be directly related to the company’s business and be of strategic importance for current or future operations. They must be measurable and verifiable and must be comparable in order to measure their real impact. This is essential because after this first phase comes the definition of SPTs. These must be sufficiently ambitious in addressing sustainability issues, as opposed to more business-as-usual objectives.

The KPIs are analysed at the outset by a specialised agency to assess their definition and level of ambition. For each KPI, a deadline is set, which may be before the maturity date of the bond itself. A thorough audit will therefore be carried out and, if the target is missed, penalties will be applied. Currently, 90% of the KPIs defined by SLBs are aimed at environmental objectives, but some issuers have defined social objectives as well, such as targets for increasing gender balance on company boards.

As outlined in the SLB principles, issuers are also expected to seek further verification of their performance level by an external and independent auditor or environmental consultant, taking into account each SPT and their respective KPI. This should take place at least once per year until the last SPT trigger event of the bond has been reached, with the aim of assessing the need for potential adjustments of the SLB’s financial and/or structural characteristics.

As SLBs are particularly relevant for companies and their transition objectives, 89.5% of issuances were made by non-financial corporates in 2021. The amounts are also relatively smaller than in the case of green, social and sustainability (GSS) bonds, which are often issued by multilateral development banks (MDBs), sovereign and supranational issuers as well as major financial institutions. According to the Climate Bonds Initiative’s figures, 44.6% of SLB issuances are between 500 million and one billion dollars, 25.8% are over 1 billion and 27.1% are between 100 and 500 million.

Given the magnitude of the task and the financing needed in order to achieve net zero by 2050, these new tools will form a critical part of the global financial toolbox.